Introduction

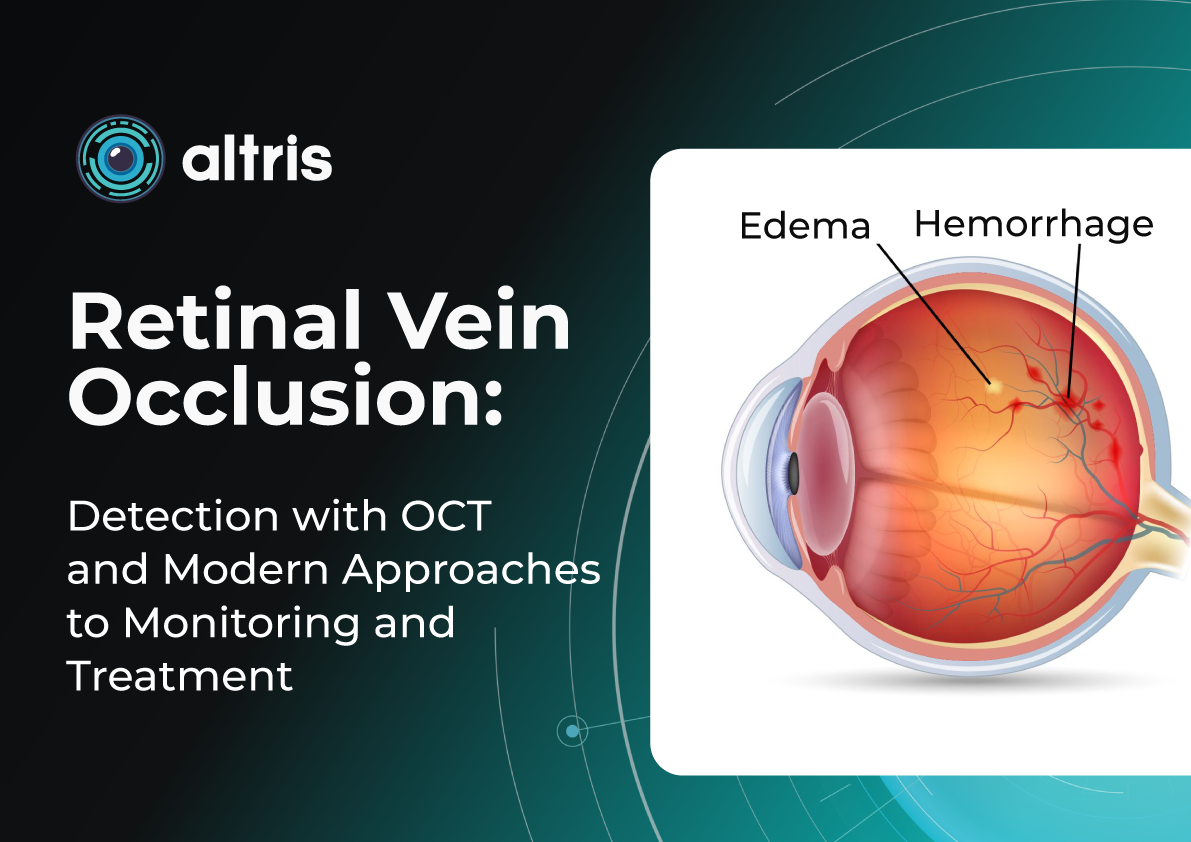

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is one of the most common and clinically significant vascular disorders affecting the eye, often resulting in substantial visual impairment. This condition ranks second among causes of vision loss due to vascular disease, after diabetic retinopathy, placing a considerable burden on both healthcare systems and patients’ quality of life. Epidemiological studies show that the prevalence of RVO increases with age, and in populations with concomitant cardiovascular disease, the risk of developing occlusion rises severalfold.

Despite a long history of study, it is the breakthroughs in instrumental diagnostics over the past decade that have fundamentally changed our approach to recognizing and managing RVO. Previously, assessment of the macula and retinal vasculature relied primarily on ophthalmoscopy. While still an important tool, it has inherent limitations.

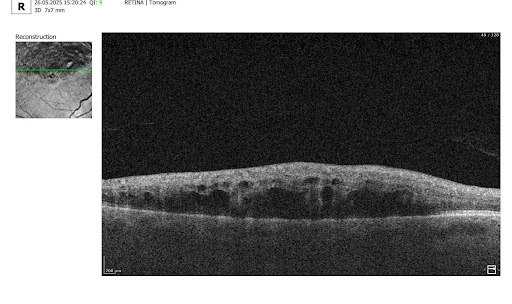

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has revolutionized diagnostic standards. With its high resolution and ability to capture subtle structural changes within the retinal layers, OCT has become indispensable for determining disease severity, monitoring treatment efficacy, and conducting long-term follow-up. It allows for the detection of minimal early signs of edema, subclinical structural damage, and initial manifestations of ischemia—changes that were practically inaccessible for dynamic assessment 10–15 years ago.

This level of precision is particularly critical for patients at increased risk of RVO. The most vulnerable groups include individuals with arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, coagulation disorders, as well as older adults, in whom the vascular walls may already have undergone degenerative or sclerotic changes.

Importantly, modern RVO treatments require objective dynamic monitoring. OCT enables precise evaluation of structural changes, tracking of therapeutic response, and individualization of treatment strategies, helping to avoid both overtreatment and undertreatment.

Thus, the role of OCT today goes far beyond simple visualization: it is a key tool for prognostic assessment, patient stratification, optimization of therapeutic decisions, and timely detection of complications.

1. What RVO Is and Why It Occurs?

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is a disruption of venous blood outflow in the retina due to partial or complete vein occlusion. As a result, the following occur:

- Blood stasis

- Increased venous pressure

- Impaired capillary perfusion

- Retinal edema, especially in the macular area

- Risk of neovascularization

Early detection is critical, as prompt treatment—particularly for macular edema—significantly increases the chances of preserving or restoring vision. Delayed diagnosis can lead to progression of ischemia, neovascularization, neovascular glaucoma, and persistent macular dysfunction.

RVO also has important systemic implications: patients with a history of RVO have a higher risk of acute cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure) compared with the general population. This emphasizes the need for comprehensive management, involving not only ophthalmologists but also other specialists, such as cardiologists.

Central vs. Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion: Pathogenesis Differences

- Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO) occurs when blockage happens at the level of the lamina cribrosa. Compression, arterial wall thickening, or thrombotic processes disrupt blood outflow from the entire retina. Typical signs include:

- Diffuse hemorrhages

- Marked macular edema

- Increased risk of optic disc and iris neovascularization due to severe ischemia

- Generally worsen prognosis than branch occlusions

- Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO) usually occurs at arteriovenous crossings, where a thickened artery compresses a vein, causing localized occlusion. Characteristic features include:

- Localized edema and hemorrhages

- Clear segmental distribution

- Prognosis is generally better than that of CRVO, though macular edema may persist

Key Risk Factors for RVO

Modern studies and guidelines identify the following as the main risk factors:

- Arterial hypertension

- Atherosclerosis and age-related vascular changes

- Diabetes mellitus (even without diabetic retinopathy)

- Glaucoma and elevated IOP

- Hypercoagulable states, thrombophilia

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Age >50 years

Rare cases of RVO associated with thromboembolic complications after COVID‑19 infection or vaccination have also been reported, highlighting the ongoing relevance of thrombotic mechanisms.

Impact on Microcirculation and Vision

RVO leads to:

- Impaired normal venous outflow

- Sharp elevation of hydrostatic venous pressure

- Damage to the blood-retinal barrier

- Leakage of plasma and cellular elements into the retinal interstitium, causing macular edema

- Development of ischemic zones

- Over time, thinning of inner retinal layers, neuroepithelial atrophy, and damage to the photoreceptor layer

These changes are best assessed with OCT, which enables precise patient stratification and treatment planning. Timely diagnosis, proper monitoring, and early therapy are essential.

2. OCT Signs of Retinal Vein Occlusion: Detecting Subtle Changes

With the advent of OCT, detection of structural retinal changes in RVO has significantly improved—even at early stages without obvious clinical signs.

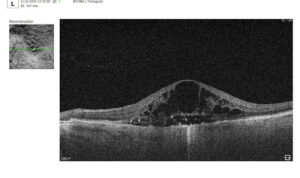

Acute Stage Changes (first weeks after occlusion)

- Macular edema:

- Cystic spaces in inner retinal layers (INL, OPL)

- Increased central retinal thickness

- Subretinal fluid (serous neurosensory detachment)

- Intraretinal hemorrhages: appear on OCT as hyperreflective areas with shadowing of underlying layers

- Ischemia indicators:

- Hyperreflectivity of neuroepithelium

- Cotton-wool spots

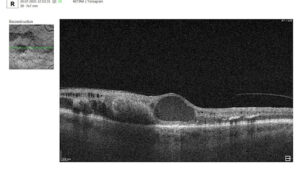

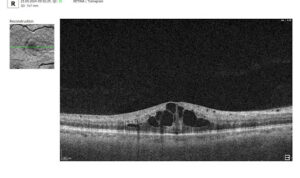

Chronic Stage Changes (months later)

- Chronic ischemic and atrophic changes (thinning of inner retinal layers)

- Disruption of photoreceptor layer (ELM and EZ)

- Disorganization of inner retinal layers (DRIL)

- Persistent edema (>6 months) indicates chronic RVO requiring therapeutic adjustment

AI for OCT thus allows both acute diagnosis and long-term monitoring of ischemic progression or tissue remodeling.

3. Assessment of Macular Changes in RVO Using OCT

OCT is now considered the gold standard for diagnosing, monitoring, and assessing treatment response in macular edema, including that associated with RVO.

OCT is highly sensitive for:

- Quantitative and qualitative analysis (central retinal thickness [CRT], macular volume [MV], size and number of cystic spaces, DRIL, photoreceptor layer integrity)

- Evaluating treatment response

- Detecting minimal residual cysts

- Predicting visual acuity outcomes

Typical OCT Findings in RVO:

- Diffuse retinal thickening

- Cystoid macular edema (localized cysts deforming normal retinal architecture)

- Serous neurosensory detachment (indicative of blood-retinal barrier breakdown)

- Disruption of EZ and ELM (photoreceptor involvement, critical for final visual acuity)

These capabilities make OCT an integral part of modern RVO monitoring.

4. Top 3 Challenges in RVO OCT Analysis

Despite its power, OCT assessment of RVO has significant limitations:

- Need for normative comparison

Interpretation requires comparison with the patient’s contralateral eye or established normal values. Systemic vascular anomalies can affect both eyes, limiting standardization. - Complexity with comorbidities

Many RVO patients have systemic (hypertension, diabetes) or ophthalmic comorbidities (diabetic retinopathy, AMD, glaucoma, epiretinal membrane), complicating interpretation. It can be difficult to distinguish RVO-related changes from combined pathology. - Requirement to consider clinical context

OCT provides only part of the clinical picture. Accurate interpretation requires integration of symptoms, medical history, systemic factors, fundoscopic findings, and other diagnostic tests. Anatomical variations, comorbidities (glaucoma, cataract), and individual treatment response also necessitate a personalized approach.

5. Treatment of RVO: Modern Approaches

Currently, no treatment restores normal retinal venous circulation. Therefore, therapy focuses on controlling complications, primarily macular edema and preventing neovascularization (retinal, iris/optic disc, neovascular glaucoma, hemorrhages, and tractional changes).

All RVO patients should receive systemic management, ideally in collaboration between an ophthalmologist and a cardiologist or internist. Monitoring of blood pressure, lipids, glucose, and coagulation factors is essential, as RVO often signals systemic vascular risk.

Treatment decisions must be individualized, considering:

- RVO subtype (CRVO vs. BRVO)

- Edema severity

- Clinical and OCT findings

- Risk of adverse effects

- Patient status (comorbidities, ability for regular follow-up)

Anti-VEGF Therapy as First-Line Treatment

Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections are the first-line therapy for macular edema associated with RVO. These drugs reduce vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, lowering vascular permeability, fluid leakage, edema, and inhibiting pathological neovascularization.

Commonly used agents:

- Ranibizumab, Aflibercept, Faricimab: proven safe and effective for CRVO and BRVO-related macular edema; studies show significant improvements in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and central macular thickness (CMT).

- Bevacizumab: used off-label for macular edema and neovascularization.

Long-term studies indicate anti-VEGF therapy provides sustained visual improvement for many patients, with injection frequency often decreasing over time.

Advantages:

- High efficacy for macular edema

- Good tolerability and safety (systemic complications are rare)

- Personalized treatment possible

Limitations / Challenges:

- Some patients respond insufficiently

- Requires frequent injections (clinic visits, financial burden, potential complications, patient discomfort)

- Chronic or refractory edema may require alternative or combination approaches

Steroid Implants and Injections: Second-Line Therapy

Dexamethasone intravitreal implant (OZURDEX) is approved for RVO-related macular edema, particularly when:

- Anti-VEGF therapy is insufficient

- Frequent injections are impractical (distance, transportation, cost)

Steroids reduce inflammation, vascular permeability, and fluid accumulation, useful in chronic or resistant edema.

Risks / Limitations:

- Cataract (especially with repeated or long-term use)

- Increased intraocular pressure (IOP), potential steroid-induced glaucoma

Laser Therapy

- Panretinal photocoagulation is effective for neovascularization.

- Its use has declined with anti-VEGF availability, which offers strong anatomical and functional results.

Surgical Approaches

- Vitrectomy may be considered in selected cases.

- Surgery carries risks and is reserved for situations where other treatments fail or are inappropriate.

Combination Strategies

- In practice, clinicians often combine anti-VEGF therapy with steroid implants or laser treatment, depending on disease course.

- This can reduce total injection burden, minimize side effects, and improve outcomes in chronic or recurrent edema.

Monitoring Frequency

- Active macular edema or ongoing treatment requires regular OCT follow-up to evaluate therapeutic response and adjust injection intervals.

- OCT schedule:

- Monthly at treatment initiation

- Individualized intervals using Treat-and-Extend protocols

- Structural monitoring to prevent atrophic changes

- Ischemic RVO patients have the highest neovascularization risk within the first 90 days; monthly monitoring during the first 6 months is critical.

Conclusions and Recommendations

RVO is a complex, multifactorial vascular disorder that can cause sudden and severe vision loss, particularly in patients with systemic risk factors. Modern management aims not only to address acute complications but also to control long-term structural retinal changes.

OCT has transformed RVO care by providing:

- Early detection of edema, subclinical ischemia, and architectural changes

- Dynamic monitoring of treatment response, allowing timely adjustments and optimization

- Improved long-term prognostication through evaluation of macular thickness, outer retinal layers, and fluid volume

OCT helps identify edema type and secondary changes—atrophy, photoreceptor damage, inner retinal thinning—allowing a more accurate visual prognosis, especially in ischemic RVO.

When combined with modern anti-VEGF agents, long-acting steroid implants, and personalized dosing regimens, OCT enables:

- Reduction of unnecessary injections via interval optimization

- Maximized treatment efficacy based on morphological findings

- Prevention of recurrence and progression through early detection of edema

Thus, OCT is not merely a visualization tool but a core element of clinical decision-making, improving patient management, preventing complications, and enabling more complete and stable visual recovery.

Clinical Recommendation: Integrate regular OCT assessments into RVO management, with attention to macular thickness dynamics and outer retinal layer integrity for precise disease control and optimized therapeutic outcomes.

References:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38714470/

- https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Retinal-Vein-Occlusion-Guidelines-Executive-Summary-2022.pdf

- https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/14/4/1183

- https://www.auctoresonline.org/article/clinical-therapeutic-orientation-in-retinal-venous-obstruction

- https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/10/3/405

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10801953

- https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/13/19/3100

- https://karger.com/oph/article-abstract/242/1/8/255831/Microvascular-Retinal-and-Choroidal-Changes-in?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40123-024-01077-9

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39717563/

- https://provider-rvo.vision-relief.com/introduction/management/